``

Hello and welcome to week 8 of ESPM 112L-

Metagenomic Data Analysis Lab!

This week’s lab is going to cover both how proteins are predicted in prokaryotes as well as how to go about learning more about interesting proteins you find in metagenomic data. Today we’re going to focus exclusively on proteins you can find in your bins, since those are more interesting (because you know a bit about which organism they came from).

In our lab, we use several popular tools to look at interesting proteins, which each have their own advantages and disadvantages. Let’s talk about them, and what they’re each good at.

Goals for today:

- Predict genes, ORFs using NCBI ORF Finder

- Learn how to use BLASTp to investigate protein sequences

- Learn how to use and interpret results from Interpro and HMMscan

- Start playing with KEGG and investigating the metabolic pathways your proteins are part of

Tools to investigate proteins of interest:

- Interproscan (most thorough)

https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/search/sequence/

This option is the best if you have a protein of interest and you want to find out exactly what it is. Interproscan uses a large suite of HMMs (probabilistic models that we won’t go over in detail today) to give you a wealth of information about the protein sequence you provide.

- Blastp (alignment-based)

https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?PAGE=Proteins

BLASTp draws on the strength of the NCBI’s public sequence database, as well as a great list of structural models that help you see the domain-level features of your protein sequence, which can tell you a lot about its function.

- HMMscan (HMM-based, very fast)

https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/hmmer/search/hmmscan

HMMscan allows you to search against a suite of domain-level HMMs, which can tell you a lot about what your protein does, and how it functions. Its companion program, pHMMer, gives you similar results along with a list of similar sequences from the EMBL-EBI’s public database, although this approach yields many fewer hits than running BLASTp and I would recommend using BLAST instead of pHMMer unless you’re pressed for time. It’s really fast, though, and if you’re doing tons of these searches, as I often am in the course of my research, it can be a real time saver.

Predicting ORFs with NCBI ORF Finder

Selecting a DNA sequence on which to predict proteins

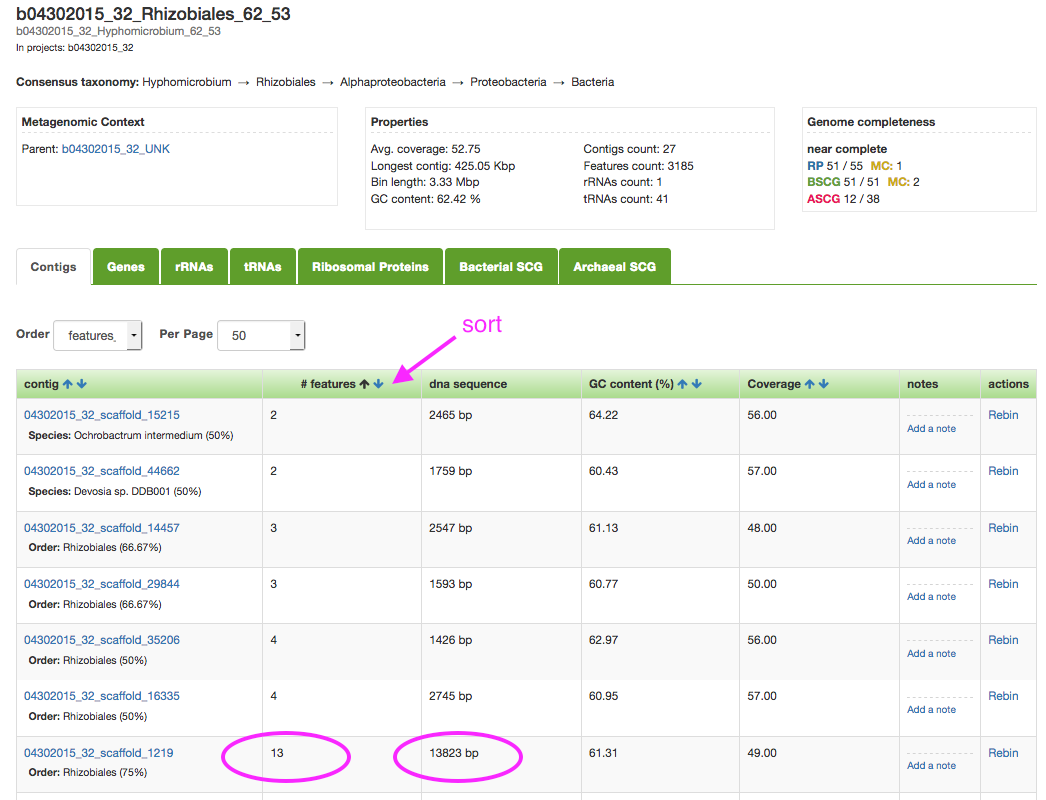

Go ahead and go over to class.ggkbase.berkeley.edu and log in. Select one of your organisms, and click on it to get a list of the scaffolds in that bin. Select a relatively large scaffold (more than ~20kbp) and click on it. A good way to do this is to sort the sequences by ‘# features’ and find a scaffold with more than 10 genes.

Performing prediction on NCBI ORF Finder

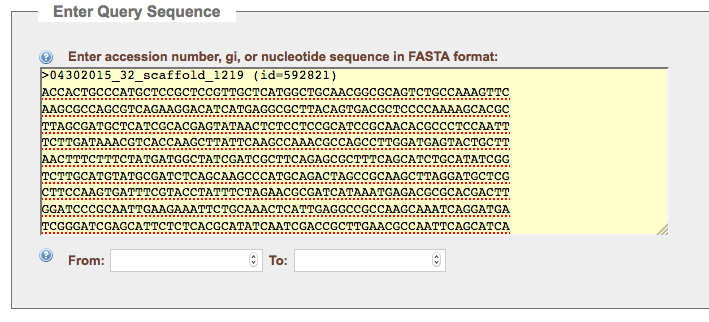

Click on the link to this contig and download the DNA sequence for this contig. Open the fasta file in a plain text editor; select all (cmd+a on Mac or ctrl+a on Windows/Linux), and copy the sequence. Go to NCBI ORF finder (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/orffinder) and paste the sequence into the Query box.

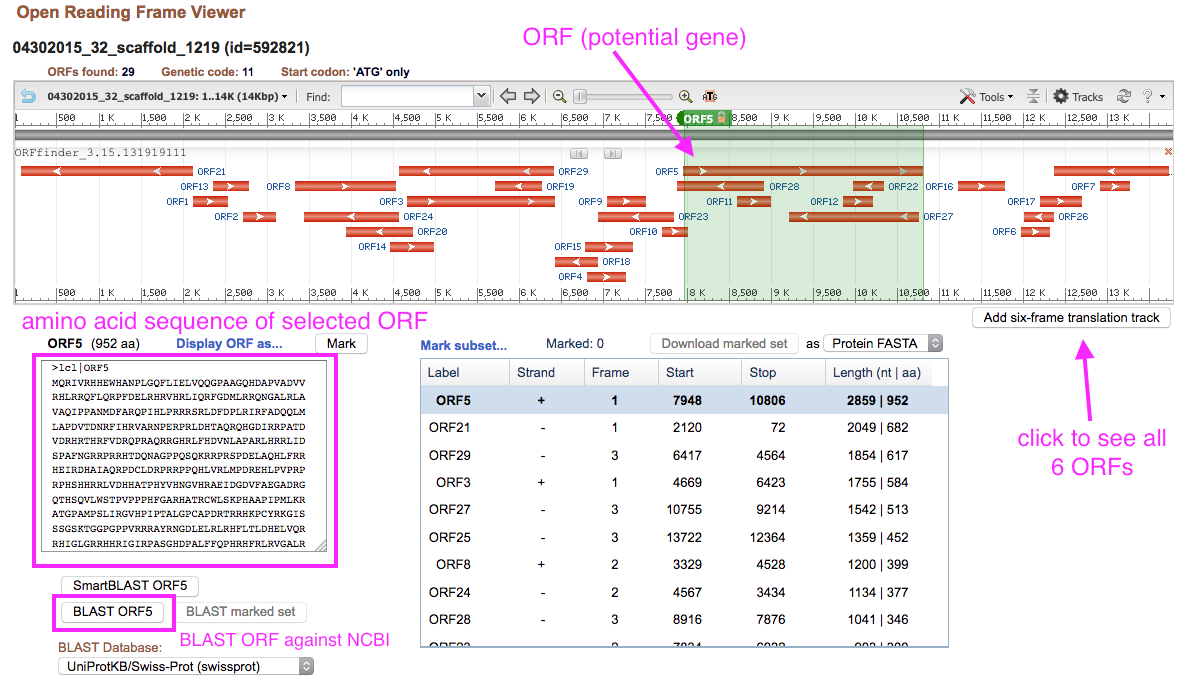

You will want to use the standard bacterial genetic code, referred to here as “Bacterial, Archaeal, and Plant Plasmid (11)”. A reasonable minimum ORF length is 150 Amino Acids, but feel free to try other cutoffs. Hit the submit button to see your potential ORFs.

The results show all of the possible genes in all reading frames. You can click on a gene in the viewer or in the list to get its particular sequence. Note: this is ALL of the possibilities across multiple reading frames, some of the resulting proteins are likely not real proteins.

Verifying proteins with BLASTp

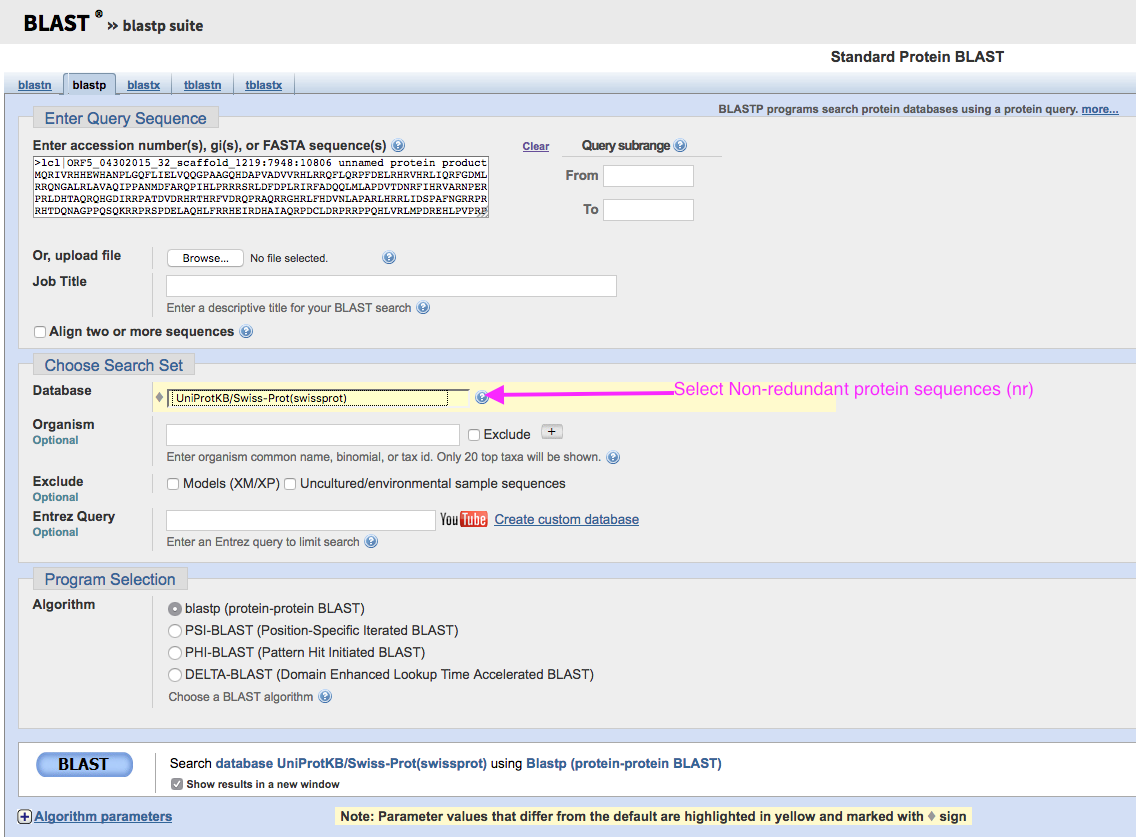

BLASTp is a piece of software that will take a protein sequence and search a database for close hits- think a search engine, but for biological sequence data.

Verify that your selected protein is real by clicking on it, like in the image below, scrolling down to the bottom left of the page and selecting “BLAST”. If your results show a bunch of other proteins with high sequence identity and defined function, congratulations! You got a nice protein. Keep working with it. Otherwise, find another one, rinse and repeat. The best candidates will have relatively little overlap with other predicted ORFs. All the standard parameters are just fine, so don’t worry about changing anything once you see the page shown in the image below- just scroll down and click BLAST.

How well do the results cover your query? Look at the colored bars in the top box to visualize this. Do you get results in the description box that agree on what this protein might be?

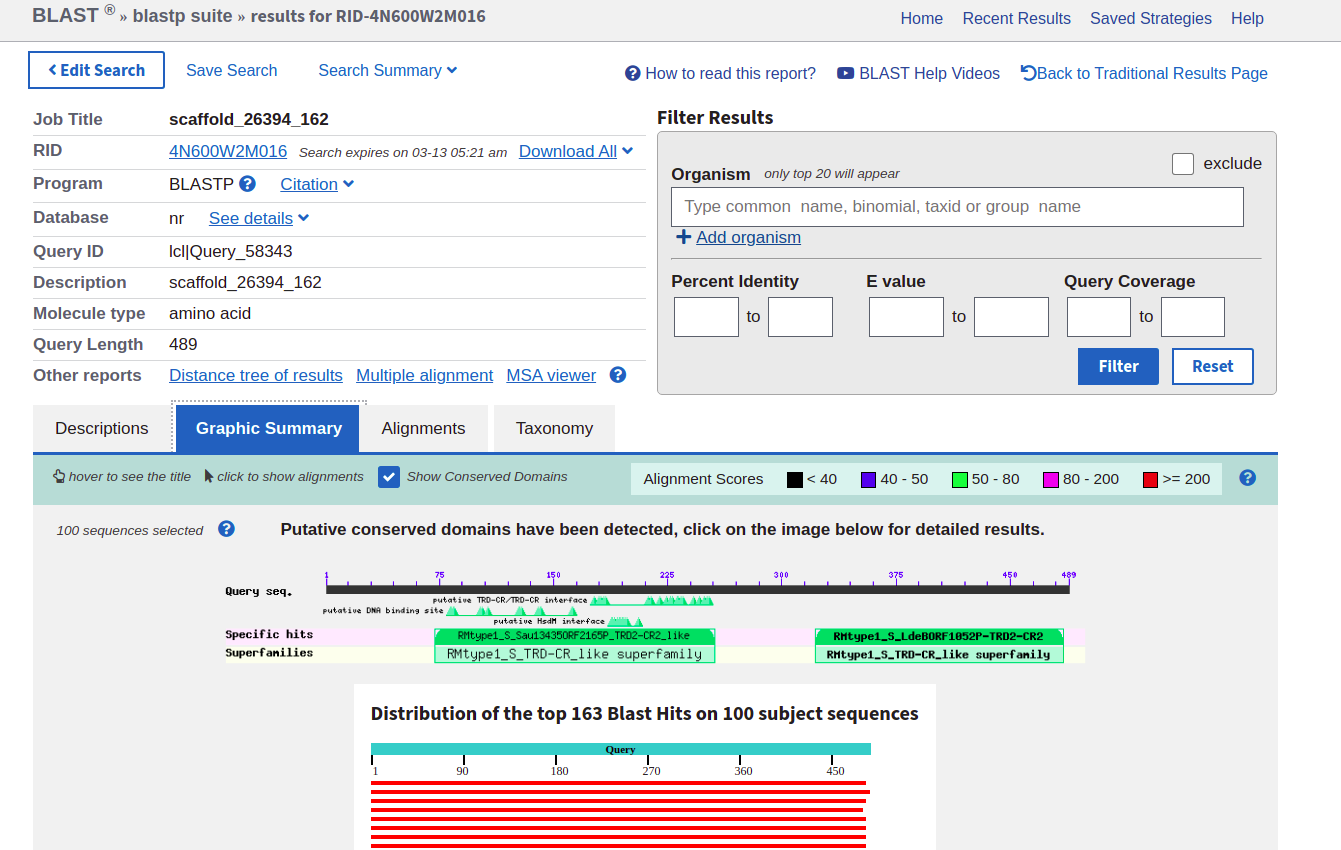

Interpreting the graphic summary from Blastp

One of the major strengths of BLAST is its integration with NCBI’s metabolic models- they’re very detailed and you can get a lot of unique info from them. Click the “Graphic summary” tab on the blastp output to see it, and it should display something like the following:

Where it shows the green bars that say, in this case, “RMtype1_S_TRD-CR-like_Superfamily”, you can click to get more detailed information. The protein I was looking at here was part of a type I restriction modification (RMtype1) system; you will see something similar but with different annotations.

Interpro

Now that you have a good ORF that you can trust is real, go ahead and navigate over to Interproscan (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/search/sequence/). Paste this amino acid sequence in as your query and wait for a little while - interpro takes a bit of time, but the results are really good and trustworthy.

You’ll get some cool results from interpro which are really interactive and highly detailed, if you have a real protein. If you have a protein with unknown function or that doesn’t look like any well-characterized proteins, you might not. In that case, just go back to NCBI ORF finder and pick another protein and repeat this whole process. (If you’ve closed the window with NCBI ORF finder or just don’t like it, you can always get these proteins from class.ggkbase pretty easily too.)

Below is a run down of the kinds of information interpro will display for you:

Protein family: in InterPro a protein family is a group of proteins that share a common evolutionary origin, reflected by their related functions and similarities in sequence or structure. (The inclusion of protein structure is one of the differences between the general search in NCBI, that only considered sequence homology, and this search against InterPro)

Protein domain: distinct functional and/or structural units in a protein. Usually they are responsible for particular functions or interaction, contributing to the overall role of a protein. Domains may exist in a variety of biological contexts, where similar domains can be found in proteins with different functions.

Repeats are typically short amino acid sequences that are repeated within a protein, and may confer binding or structural properties upon it.

Sites: groups of amino acids that confer certain characteristics upon a protein, and may be important for its overall function. Sites are usually rather small (only a few amino acids long). Some types of sites in InterPro are active sites (involved in catalytic activity, binding sites (bind molecules or ions), post-translational modification sites (chemically modified after the protein is translated), and conserved sites (found in specific types of proteins, but whose function is unknown)

KEGG

Once you have a relatively interesting protein, the best way to dig further into it and find out what its role is in the cell is to look it up on KEGG. Just google “kegg” + the name of your gene, and you’ll generally see a few results that line up with what you’re looking for. (This will be part of the demo at the beginning of class.)

One of the greatest things about KEGG is the fact that it provides information on publications related to that gene where you can read about the gene’s function, and also (not always, but often) links to “pathways” and “modules” containing that gene. Pathways and modules are groups of genes that work in sequence to perform a given task - fixation of nitrogen, for instance, is a good example of a module; photosynthesis, being much broader and involving many more genes, is classified as a pathway.

Here’s an example of an important gene, Nitrogenase, involved in the fixation of atmospheric Nitrogen by bacteria: https://www.genome.jp/dbget-bin/www_bget?K22898

Notice near the top of the page the KO number (K22898) which is a good way of keeping track of individual genes, the pathway number (ko00910) which contains many other nitrogen metabolism genes, and the module number (M00175) which indicates that this gene is involved in nitrification, the process of converting atmospheric N2 to ammonia, NH3.

Turn-in for today:

- Find a protein that has an informative annotation. (This is subjective- you decide whether it’s informative or not. Do the annotations give you any helpful clues?)

- Are there highly related blastp hits? If so, do they come from the same type of organism? (The organism taxonomy is in the sequence names.)

- What is the suggested function for that protein from interproscan? (You can find this at the bottom of the interpro results page.)

- Which, if any, HMM models hit this protein on HMMscan?

- Are there proximal genes with related function on the scaffold where you originally obtained this sequence?

- Return to the pathway you investigated last week using genome summaries. Can you find that pathway on KEGG?

- Can you identify in your genome a key gene in your selected pathway (e.g. mcrA for methanogenesis?)

- Choose one other gene in this pathway from KEGG (as described in the demo at the beginning of class) that is not immediately next to the gene you chose in the previous part of this question. Can you find it with a genome summary? If not, create a custom list and look for it in your genomes. Send me the custom list if you created one, and tell me which gene(s) you chose to search for.