``

Hello and welcome to week 7 of ESPM 112L-

Metagenomic Data Analysis Lab!

- How to run dRep (for your reference)

- Analyzing dRep output

- Using ANI clustering to make a dereplicated bin set

- Comparing synteny between bins with at least 99% ANI

- Today’s turn-in

This week we’re going to be looking at methods of dereplication of metagenomic bins. We often sequence environments that contain lots of very similar microorganisms (E. faecalis, anyone?) and it becomes less than desirable to spend time and effort analyzing a bunch of extremely closely related genomes instead of looking at the general population.

For this and other reasons, which I’ll discuss in much more detail in today’s lecture/demo video, we use a program called dRep designed by the inimitable Dr. Matt Olm, a former ESPM 112L GSI and Ph.D. student in the Banfield lab.

Today’s lab primarily involves analyzing the output of dRep and interpreting it; this can help give you an idea of which closely-related organisms are present in multiple samples across your dataset.

First, let’s go over dRep, how I ran it, and how you can run it (on your own time if you so desire, not during the lab period please!).

dRep is a program that utilizes genome wide average nucleotide identity (ANI) to group bins into clusters based on how similar they are. In this way, we can figure out which organisms are present across multiple samples because the bin from each sample will fall into the same ANI cluster.

If you want to run dRep on your own, the documentation is here:

How to run dRep (for your reference)

dRep uses DNA-DNA comparisons to find very closely related genomes in your dataset. This is performed using MASH, a fast alignment algorithm that gives approximate (i.e. not entirely perfect) comparisons between two genome-size chunks of DNA in a reasonable period of time. This is a really hard task, and takes a very long time if you do it exactly!

What you’re going to see today are clustering results; this is done by taking the similarities between genomes and clustering them into highly related groups. First, “primary” clusters are formed out of loosely related organisms, then more stringent comparisons are done among these smaller clusters.

The secondary clusters use a different algorithm, gANI, to perform similarity comparisons- this gives more accurate values, and is only feasible when run on a small number of genomes.

dRep is run using genome fasta files containing DNA (not protein) data. You call the program by saying dRep dereplicate, provide an output directory name (I call it dRep_output), and a folder full of genomes (-g all_contigs/*.fasta). In this case I put all the bins for all samples in a single folder and ran dRep on that.

The -p flag refers to the number of threads you’re using- be careful not to use too many if you’re running this on your local machine. If you’re running it on the cluster, 24 is the maximum number available, and remember not to use those all at once if others are using the cluster too.

Here’s the final command:

# DO NOT RUN ME PLEASE! THIS IS JUST A DEMO!

dRep dereplicate dRep_output -g all_contigs/*.fasta -p 24

Analyzing dRep output

Now you can go in and look at what dRep has generated after comparing all of the bins from all 9 of our samples. Go ahead and navigate to /class_data/dRep_output and take a look. The dereplicated_genomes/ folder contains the genomes dRep has chosen as representatives- i.e. the best genome for each group. The figures/ folder has all the pictures you’ll need to look at in the following section. Remember, to download any of these pictures, here’s what to do:

Downloading and viewing dRep output

Download the files Primary_clustering_dendrogram.pdf and Secondary_clustering_dendrograms.pdf. Let’s take a look at them.

The primary clustering dendrogram is a clustering of the bins based off of MASH. It should look something like the following and have every bin from every sample in a single dendrogram:

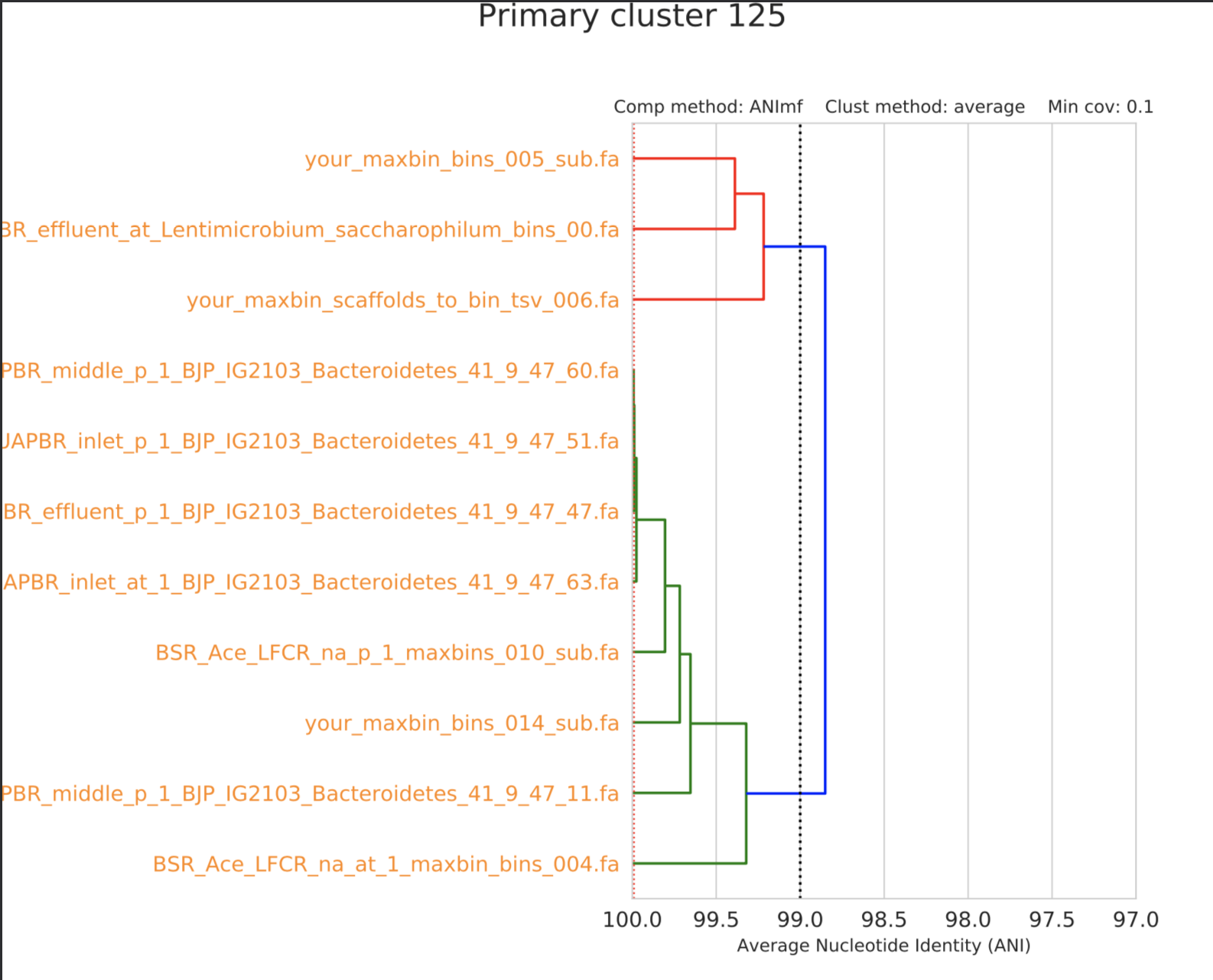

The secondary clustering dendrogram is the ANI clustering performed on each of the identified MASH clusters. This file should contain quite a few different dendrograms, each relating to a different MASH cluster and should look something like the following for a single cluster:

We generally consider bins that share 99% or greater ANI to be from very closely related organisms (i.e. same species). In the above secondary clustering example, all of those bins would be considered to be from the same set of closely related organisms. In the below example, there are bins from two different organisms present:

If you don’t understand why there are two groups in this clustering please ask me. This is an important concept to understand. The important part is being able to read a dendrogram- the vertical line at 99% ANI indicates a dividing line between the two groups (on top, the Lentimicrobium group and on bottom, the Bacteroidetes group).

Using ANI clustering to make a dereplicated bin set

This secondary clustering file is what we will use to create a dereplicated bin set across all 17 samples. We will consider bins that share 99% or greater ANI to be from the same organism type. With that in mind, all we need to do to make our dereplicated bin set is pick one bin from each cluster of bins that share >99% ANI to be that clusters representative bin.

We want the representative bins to be high quality, so pick the best bin by looking at each in ggKbase and picking the bin with the best single copy gene profile. If there are ties, pick one arbitrarily.

This dereplicated bin set will be useful for future analyses, but we will not be using it for the rest of this week’s assignment.

Comparing synteny between bins with at least 99% ANI

Synteny is the shared order of genes among two or more organisms - essentially, a syntenic block is a group of genes in the same arrangement in multiple organisms. Orthologer is a program that takes two ordered lists of protein sequences, compares them to each other, and displays genes in the first organism that are reciprocal BLAST best hits in the other. While this program can accept multiple genomes as an input, I recommend only two genomes at a time.

Look at your file Secondary_clustering_dendrograms.pdf. Each cluster has a separate dendrogram- choose one containing a genome from your sample- we are going to analyze two genomes from this cluster in the following section of this lab. (All the file names start with the sample the bin was obtained from!)

Important note about file locations and names

The DNA sequence files are in /class_data/dRep_output/dereplicated_genomes and end in .fna; the protein/AA sequence files are in /class_data/dRep_output/dereplicated_proteins/ and end in .faa.

Running orthologer

Choose two genomes that are in this same primary cluster. Now, get the protein fasta files for those bins from the folder /class_data/dRep_output/dereplicated_proteins and copy them into your home directory.

I like to make directories before I run analyses, so let’s make one in our home directory (mkdir ~/orthologer) and copy these bins into it:

mkdir ~/orthologer

cp /class_data/sample_bins/all_proteins/[YOUR FIRST CHOSEN BIN] ~/orthologer/

cp /class_data/sample_bins/all_proteins/[YOUR SECOND CHOSEN BIN] ~/orthologer/

Now you’ve got those two (protein) fasta files in your orthologer directory, let’s go ahead and run orthologer.py to compare them. You’re going to have to use my installation of python, which is why I have those huge paths down below- just roll with it.

Now take your two protein fastas (should end in .faa), which we’ll call [FASTA1] and [FASTA2], and do the following:

cd ~/orthologer

python3 /home/jwestrob/bin/bioscripts/ctbBio/orthologer.py reference [FASTA1] [FASTA2] > genome_comparison.tsv

Now you have a file called genome_comparison.tsv that you can download and open up in excel/google sheets. Give it a look- see how large the syntenic blocks are that these two genomes share. Remember, you can look up gene names in ggkbase and see what they do. (I will give a quick demo on this at the beginning of class.)

Today’s turn-in

-

Can you find any operons that these two genomes share? (From your orthologer output) What genes are encoded in these operons?

-

What is the taxonomy of the two genomes you chose? (Look them up on ggkbase)

-

Can you find any particularly large clusters in the primary clustering dendrogram? (

Primary_clustering_dendrogram.pdf)Give the name of at least one bin from this cluster and look up its taxonomy on ggkbase.